When we analyze its existing meaning, we can see that we need, and will have to, rearrange the word once again.

It was drawing, or disegno, as it spread in the structure of Italian Renaissance buildings, that gave us the word “design,” at least that’s the enthusiastic explanation I got as an architecture student in the late 1990s.

While there was a key change in the meaning of “design” between 1300 and 1500, it had less to do with language and more to do with a basic change in the making of the things themselves. The dating between the drawing and the design did not lead to a word, or even expand its meaning. Rather, it reduced the word as it was used before, and in a way that it would possibly now be vital to reverse.

The Latin root of “design,” dē-sign, conveyed to other people like Cicero a set of meanings much broader and more summarized than those we give to the word today. These ranged from the literal and draped (like the layout) to the tactical. (invent and achieve a goal) to the organizational and institutional, as in the strategic “designation” of other people and elements (where the root “design” remains visibly anchored). All these meanings represent a broad meaning of imposing form on the world, on its establishments and arrangements.

However, the use of design to shape structure in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries initiated a linguistic shift, with this sense of “design” eclipsing almost all others.

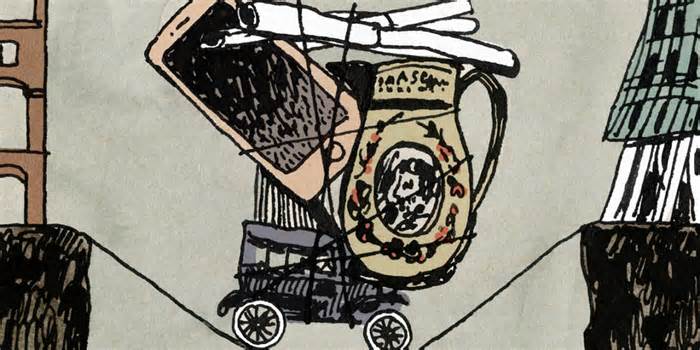

A first snapshot of this ongoing transformation is a scroll dating back to 1340. Bending, pleating and drilling with nail holes, he registered a contract between the boss and 3 large developers for the structure of Palazzo Sansedoni in the center of Siena. In its partial diminution, the parchment records the legal and monetary arrangements surrounding the palace structure; In its half, it represents an elevation -a drawing- of the façade not yet built, with annotations and dimensions.

Drawings, by necessity, recorded the goal of developers long before 1340: traced on the floor, wall or, in all likelihood, more portable surfaces. These inscriptions, however, were secondary and adjacent to the process of structure. But the growing prosperity of economies such as Siena’s in the 1300s made it very likely that eminent masters would balance several projects simultaneously, so it has become mandatory to rely on the authority of an elaborate document, a “design” in various senses of the word, which was then used to govern activities at the site of the structure. In fact, part of the paper of the Sansedoni scroll to describe the role of an anonymous fourth builder, who would remain on site to direct the paintings while the 3 named signatories of the contract were busy elsewhere. Along with this transformation, the master of the structure site replaced through the architetto, or architect, who would produce and record the design of the structure, with authority granted basically through documents and drawings.

As a result, architects may adopt an owning attitude towards the word “design. “If there is a justification for such sentiments, it is that architects were the first to practice design in the new sense, as a strategic mode based on drawing to shape elements and environments other than their direct manufacture. However, if architecture pioneered design as a career and curriculum in its own right, it would soon have company. or sketches, as specified through its curriculum and as a component of what we now call the “design process,” the chimneys of factories emerging farther from Paris would mark the same larger shift in the economy of the physical world and the concept of design within it.

As early as the sixteenth century, designs and models of family porcelain passods traveled between Europe and the furnaces of Jingdezhen in China, helping to specify bureaucracy and ornament patterns, what we would now call designs, to be created for express markets. In the eighteenth century, the British pioneer Josiah Wedgwood employed “master” artists and potters to make illustrations and models. t go wrong. ” But in addition to getting rid of the error box for painters, he put an end to his individual expression. And it was the next literal mechanization of production that firmly separated design paintings from production, with profound consequences for the definition of design, as a word and as a schematic of our society.

While this design concept has now spread to our society and economy, we can take only one industry as an example. It was Henry Ford’s Model T, whose simplified design of 1907 allowed gasoline-powered cars to be more than just traditional toys for the wealthy. it was Alfred P. Sloan’s equally vital innovation at General Motors, in 1924, to introduce design in the sense of new annual models and other costs and degrees of prestige for mechanically similar vehicles, from Chevrolet to Cadillac, an excursion of unnecessary advertising force.

Thus, while calling a bag or sunglasses a “designer” would possibly convey a superficial brand rather than the price of curtains, we deeply appreciate “design” as one of the few activities that can make navigable the complex realities of modernity. It’s no coincidence that corporations seeking to make products that are transformative and accessible (Tesla, Apple, even IBM in their day) proclaim a surface-finishing elegance as the (alleged) manifestation of global technological sophistication, even as they exploit the advertising price of taste and status.

However, despite all the technological transformation of the world, the underlying genesis of almost all new buildings remains a set of designs and specifications that would have been recognizable in Siena in the fourteenth century. It also means that the word “design,” as it is used, still fits this millennia-old definition, even if it extends far beyond construction. Which, ironically, moves away from drawing as the only means of design. In recent decades, architecture and its sister professions have begun to adopt virtual teams that are beginning to facilitate design far from boundaries; Technologies such as 3D printing and building robot gathering dissolve part of the classic distance between design and manufacturing.

Prosthetic designers are devising new tactics to make other people feel more comfortable with themselves.

At the same time, such advances have coincided, perhaps not coincidentally, with the commercialization and adoption of so-called “design thinking,” whose practitioners paint away from the newsroom. The irony of this practice is that the team derives from the meaning of “Design drawing—ways of sketching, outlining, and rearranging relationships graphically, with post-its, or otherwise—are the ones that are so effective when implemented in problems far more abstract than the immediate physical or visual environment.

But it’s not just the good fortune of design offices that gets us back to a broader view of design. The reduced post-industrial importance of design is inseparable from a corollary of minimizing the planet’s finite resources, whether the quarried stones stacked into shape into a Sienese palace or the rare earth metals that anchor icons like the iPhone. While design can be a source of great good, it also does the duty of our existing ecological crisis; Perhaps not everything new is much more wonderful than the old.

If today’s designers move further downstream of delineation through prototyping and direct manufacturing, we would also gain a lot by asking the design further upstream, so to speak. building, resources and decisions on which a designed global depends.

From the continuous reuse of fabrics in a “circular” economy, to a reorientation of architecture towards adaptive reuse, to the redesign of food away from unsustainable meat, we want to reshape not only items, but also the culture and establishments that create them. . It is not through the possibility that such paintings take up the dē-sign in its original sense: not only the search for a more beautiful form, but the shaping of a more beautiful and sustainable world.

Nicholas de Monchaux is professor and director of architecture at MIT.

This story component from our March/April 2023 issue.

A technique that promised to democratize design has done the opposite.

The formatting tips for OpenAI’s giant language style are impressively presented, but don’t take them too seriously.

The culpable use of generation is a concrete business consideration, driven through a varied set of priorities and directions.