Electric cars have emerged in the face of Ford’s whims, Edison’s filthy batteries, Big Oil and the old theme of charging stations.

Finally, the world is embracing the electric car. Governments around the world have committed to upgrading their gasoline fleets with hybrid or all-electric vehicles and, as a result, Toyota, Nissan and Ford are launching hybrid and all-electric cars. Elon Musk’s Tesla is one of the fastest growing automakers in the world and manufactures the most productive mass-produced cars in history.

But electric cars aren’t new. They have been around as long as their internal combustion cousins and, in the early twentieth century, were thought to be long-term car transport. only in the experimental sense. Convenient, reliable, and relatively electric cars whispered along the roads from Los Angeles to Sydney in 1910. Your tech fans would read today’s headlines, bewildered that in 2016 we’re just catching up with the past.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, urban transport (especially in crowded urban areas) still consisted basically of horse-drawn carriages. For many, electric cars perfectly replaced horses: they were silent, did not want to be fed and, even so, they were intended as a very “clean” option (read: no poop on the streets, a serious challenge at the time). Even the disadvantages of electric motors made them perfectly suited for city travel: streets and arteries at the time weren’t built for cars traveling over 20 mph anyway, and horses and trains were preferable for long trips, so the limited diversity of electric vehicles was more or less an issue.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Paris and London Post Office had fleets of electric wagons for mail delivery. New York supported a burgeoning electric taxi industry (90% of the cars in taxi fleets were electric). In urban spaces in the Americas and Europe, delivery is beginning to upgrade its fleets of horse-drawn rail cars with electric delivery cars capable of carrying thousands of pounds of cargo.

So why did it take the world a hundred years to (re)adopt electric vehicles?It turns out that the electric car of the 1900s suffered the same obstacles that continue to hamper the industry in 2016.

It is vital to perceive that at the beginning of the twentieth century, electric power was still considered a novelty: only about 3% of families had access to electricity. Just like now, it is very difficult to find a recharge. Thomas Edison, the very father of electric power, pushed for electric power to be the energy source of the future, but especially in the booming auto industry. However, he envisioned a world with the right infrastructure: electric charging stations as a built-in component of each and every home, building and public space. Their vision resembles an electric vehicle sales pitch:

Ironically, it was Edison’s foray into electric car production that contributed to its downfall. He teamed up with a former worker named Henry Ford to design a reasonable mass-produced electric vehicle. Electric cars were ridiculously expensive at the time, between $1,000 and $3,000 (compared to $25 to $100 for a horse and about $600 for a Model T). Then Texas discovered that crude, in gigantic quantities, and fuel have become less expensive than power generation. The oil industry, perhaps aware of its herbal disadvantages, set out to create one of the most tense teams in the history of capitalism.

To his credit, Ford, which was on its way to becoming one of the richest men in the world by generating reasonable gasoline-powered cars, invested the equivalent of $31. 5 million in electric vehicle allocation with its former boss (100 years later, Ford Motor Company announced it would invest about $135 million in its “new” EV allocation). That ended up being the loss of the allowance.

According to the theory, Ford would only use batteries designed and manufactured through Edison, ordering 100,000 batteries without testing them well on its prototype. It turns out that Edison’s batteries, to use proper technical jargon, sucked the back pacifier. Edison’s batteries literally couldn’t move the car. Ford engineers begged him to use larger batteries, but Ford refused. When he learned that some dishonest workers had tested the new electric prototype with heavier lead-acid batteries from another company, Ford turned its Twinkies upside down. Instead of making an investment in new batteries from one of Edison’s competitors, it opted to reduce its losses and shut down the project.

Even with Ford’s failures, dozens of brands were generating electric vehicles, and the generation was getting bigger and less expensive every year. While Edison couldn’t produce good enough batteries, his vision of citywide power grids has become a reality: Between 1910 and 1920, access to electric power increased from 3% to 35%. While domestic charging stations resembled those of The Jetsons just 10 years ago, they fit a practical and fairly feasible option before World War I. York Times article:

Oddly enough, one of the main reasons for the drop in electric cars had little to do with the technology’s limitations, or even cost, but rather with gender marketing. In fact, the war between electric and gasoline car brands is where we started. to see the progression of gender facets of car culture. As Deborah Clarke writes in her e-book Driving Women: Fiction and Automobile Culture in Twentieth-Century America:

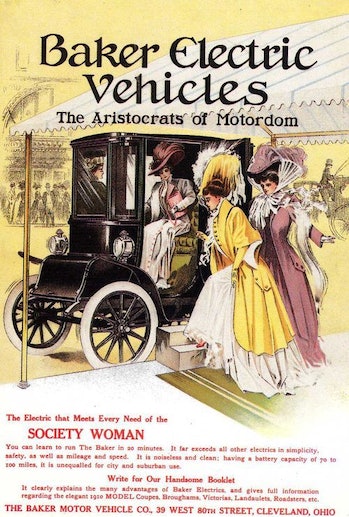

Electric wagons began to advertise themselves almost exclusively as literal four-wheeled contraptions for ladies, who desired the “illusion of freedom” to move around the city as they pleased, but who might not take care of the strength or headaches of the “real. “Petrol-powered cars, with all those confusing levers and pedals and exhausts and slamming doors and things like that.

Even today, brands are struggling to break the stigma of hybrid and electric cars that are too feminine for red-blooded American men. A major hurdle for corporations like Tesla, GM, Ford and Toyota is proving that even hybrids and electrics can offer the same sense of machismo (read: good enough penis extension) as their gasoline counterparts.

The Great Depression put an end to EV OG. Once the stock market collapsed, the money and drive to expand more efficient electric vehicle generation and infrastructure disappeared. At the end of World War II, it is evident that the king of the oil industry, and although Henry Ford is unlikely to have been a pawn in the global oil clique, there is in fact evidence to recommend that large oil corporations played a leading role in preventing electric cars. The road to the next, oh, 70 years or so. Meanwhile, the modern oil-fueled economy has devastated grasslands and oceans, financed and justified wars, and injected enough carbon into the environment to ensure the collapse of the entire climate.

So, yes, the global thing is even though everything comes back in the EV game. Meanwhile, Edwardian futurists watch from the ether, wondering what, in the blue flames, took us so long.