Before the U.S. was even a nation, labor strikes drove significant social and economic change. From the founding of the first major U.S. labor union, the Knights of Labor, to the development of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), labor unions have helped employees stand up to the companies they work for in order to secure higher wages, safer working conditions, and bigger benefits. Although the frequency of strikes and positive outcomes have fluctuated over the years, walkouts are still vehicles through which American workers can try to pressure management into offering better pay rates and improvements in working environments.

Some periods in U.S. history have experienced higher incidents of painting stoppages than others, such as the years immediately after World War I and World War II. Strikes in the United States have become more common in those periods than at other times, with wages and trade union popularity sometimes at the center of labor disputes in industries such as mining and automotive.

The Milwaukee Bucks’ resolve to stay off the basketball court on August 26 showed a new type of strike, a guy who goes beyond withholding hard work to get concessions from an employer. The strike, the Bucks said in their locker room, aimed at not easy action through Wisconsin lawmakers in reaction to the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a black father who was shot in front of his children in Kenosha, Wisconsin. “Despite the overwhelming demand for change,” the Bucks said, “there was no action, so our attention today can’t be in basketball.”

Strikes are not a past. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 20 primary hard-working movements have been performed in 2018 and 25 in 2019. Most of these movements concerned staff in the education, physical care and social facilities sectors. The year 2020 saw a handful of primary movements, in addition to threats of strike through teachers’ unions, as in Chicago and New York, in reaction to plans to reopen schools by the pandemic.

Funding from U.S. public schools And instructor compensation has been a long-standing problem, as evidenced by the series of instructor changes over the decades. In 2018 and 2019, the number of instructor outings has increased, starting with the West Virginia instructor strike in 2018, in which 20,000 public school professionals demanded higher pay and more physical care. Teachers in Arizona, Colorado, California and other states followed suit, all struggling for higher wages. In 2019, Los Angeles instructors went on strike for a week and Chicago instructors went on strike for 11 days.

Read on to be informed of some of the largest and highest worker movements in U.S. history, from the Polish craftsmen’s strike in Jamestown in 1619 to the 21st century movements in the automotive, communications and education sectors. Knowledge is gathered from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, publications such as Wall Street Journal and Fortune and AFL-CIO.

You also like: 30 wins for workers’ rights earned through trade unions over the years

In the first strike recorded in pre-revolutionary American history, Polish glassmakers and manufacturers of tar, tar and turpentine for shipbuilding refused to continue running for the British Virginia Company until they were entitled to vote in the iconic Elections of the Virginia House of Representatives. Bourgeois. The settlers had hired Polish staff to come to Jamestown to rebuild the colony’s economy; however, only those of English descent were eligible to vote in the elections at the time. The strike forced the company’s hands and staff received full voting rights.

Isaac Friend and William Clutton led this strike by hired servants in York County, Virginia, due to below-normal food rationing; some only earned corn to eat and water to drink. The uprising was largely unsuccessful. Subsequently, laws were passed restricting the rights of servants, allowing the brutal remedy of slaves, and advising masters to closely monitor their servants. The revolt was followed by other primary uprisings, such as the 1663 one opposed to the governor of Gloucester County.

The carpenters of Hibernia Iron Works of New Jersey were among the first painters of American structures. Construction unions played a leading role in New Jersey’s industrial federations that formed in the mid-19th century, such as the New Jersey State Labor Federation, which became the American Labor Federation and the Congress of State Industrial Organizations. The New Jersey Building and Construction Trades Council and its related union led the fight for the eight-hour painting day, higher salaries, safer painting environments, and solid pension plans.

In the first wage increase strike in U.S. history, Philadelphia printers arranged for paint stoppages to call for an accumulation of 35 shillings per week at $6 per week. The strike was a success and resulted in similar wage disputes in Philadelphia, such as the Cordwainers’ strike in 1806, the first union accused of a fraudulent project.

This carpenter strike, also in Philadelphia, drove the 10-hour workday and the first official strike by the structure guilds in the United States. The action was a success and marks the first time a local union has participated in collective bargaining. However, as unions began to gain ground in the United States, employers began to turn back. This led to more trade-focused disruptions, such as the textile strike of 1824.

Faced with 13-hour painting days and pay cuts, women who ran Lowell Mill in Massachusetts protested the recovery of their original salaries and brought together women from other factories to join them in the fight. Their employers ended the strike and sent the women to paint. Although the efforts of these staff triggered long-term political uprisings in the form of the Lowell Women’s Job Reshaping Association, which sought to identify 10-hour painting days, their struggle for social justice was slow to bring about really extensive change. For example, New Hampshire passed the 10-hour painting law in 1847, but employers were not required to enforce it.

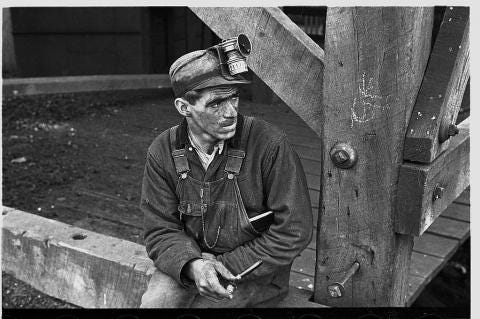

A 20% pay cut was at the center of the coal miners’ strike in the northeastern valleys of Ohio and Pennsylvania. The miners demanded a slight pay increase consistent with the ton of coal, but their efforts eventually failed. With thousands of miners on strike, mine owners hired African-American and Italian replacement staff, prompting a backlash from strikers. Employers’ use of migrant replacement personnel has prevented minors from being effectively organized.

When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad cut workers’ wages twice last year, their workers stopped exercising until their last pay cut was canceled. After the West Virginia government attempted to repair order by sending defense force troops, the attack spread to Baltimore, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Chicago. In some cities, strikers became violent and destroyed the assets of the railways. The strike ended mainly by government intervention and defense forces, and the B-O Railroad hired strikebreakers.

Jim Crow’s legislation was fully in effect in the United States in the last 19th century, but that didn’t stop an African-American lavender organization in Atlanta, known as the Wash Society, from joining in to insist on higher wages and office autonomy. Faced with the disapproval of the press and arrests by protest leaders, the washerwoman organization approached the mayor of Atlanta, which was not easy for him about the city’s laundering activities in exchange for a $25 annual leave payment. The city eventually accepted this condition and the Washing Society paved the way for innovations in operating situations in other Atlanta industries.

In this strike involving over 200,000 workers, railroad employees in five states rose up against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific Railroads, owned by Jay Gould. They revolted on the grounds that a worker was fired “without due notice and investigation,” as per the agreement between the then Knights of Labor and the Union Pacific. Gould hired strikebreakers to keep the railroads running, and, ultimately, the Knights of Labor disintegrated. But shortly thereafter Samuel Gompers and Peter McGuire founded the American Federation of Labor.

African-American sugarcane staff in Louisiana faced appalling career situations and incredibly low wages: they earned about $13 a month paid on certificates, a coupon valid only at the plantation owner’s store where costs were accumulating. The workers were indebted to the planters. Sugarcane staff opposed the plantations and demanded the cessation of certificate payments, the increase in daily wages and the payment twice a month. The Louisiana Sugar Producers Association denied such requests, leading to one of the bloodiest hard-working disputes in U.S. history: the Thibodaux massacre, where the government defense force attacked and killed black sugar personnel who had been evicted from the plantations.

In September 1891, a black sharecroon organization in Lee County, Ark., perhaps related to the Alliance of Color Farmers, rebelled against the owners of cotton plantations to ask for higher wages. However, the strike largely failed; a white-led mob ended the revolt and killed at least a dozen black cotton pickers. The severity of the reaction was a precursor to long-term retaliation by landowners who opposed African-American labor disputes, such as the Elaine Massacre in 1919.

In one of the most critical conflicts in America’s hard work history, metallurgists have opposed the Carnegie Steel Corporation in reaction to advanced steelmaking technologies and large recruitment of unskilled personnel and declining wages. The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers organized the strike, making it one of the first highly organized and well-directed labor revolts in American history. Carnegie Steel eventually refused to recognize the union, and American steel personnel (and those from other heavy industries) were unable to vent the popularity of collective bargaining until the 1930s.

When the panic of 1893 caused a deflation of the value of silver and an influx of silver miners began to paint in the gold mines, the gold miners’ pay fell and attacked their patterns. Free Coinage Union leaders have partnered with the Western Federation of Miners to claim $3 according to the proposed $2.50 paint hours per day. In the end, he won the union, which led to the organization of other painters, as well as the expansion of the WFM in the years after the strike.

When the Spanish-American war led to an increase in newspaper sales, some publishers increased the wholesale value of one hundred newspapers from 50 cents to 60 cents. As a result, newspaper vendors in Long Island City, New York, began the strike opposing Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, editors of the New York World and the New York Journal, respectively. Other strikers have risen in other parts of New York. The protests ended when Pulitzer and Hearst showed up to keep the value of a hundred newspapers at 60 cents, but they would buy newspapers again that newspaper sellers simply don’t sell. DC Comics idealized the gavronniers in the 1942 comic strip “Newsboy Legion”, and Disney created the musical film “Newsies”, telling the story of the strike.

In one of the most violent American tram movements of the first third of the 20th century, drivers left their jobs, were not easy 8 hours of painting a day and a salary of $3 a day. This did not bode well for the city of San Francisco, which depended on its trams to operate. When the president of United Railroads summoned 400 strikers, the strikers took to the streets. They attacked the strikebreakers on Tuesday, May 7, in what the San Francisco Chronicle called “bloody Tuesday.” After 31 dead, the strike still failed and the tram union disbanded.

In what was also known as the Bread and Rose Strike, members of Industrial Workers of the World opposed homeowners at the Everett plant in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in reaction to relief in weekly hours and 32% weekly. payment of the week- Cut. In the early 1900s, textile staff survived with very little food and died before the age of 40. Workers from dozens of nationalities, many of whom were women, were at the center of the strike. After President William Howard Taft asked for an investigation into the factory’s operating conditions, homeowners granted staff a 15% pay increase and an increase in overtime pay. The strike paved the way for thousands of textile workers in New England and other industries to get better wages.

As a result of wartime inflation, American metallurgists have experienced low wages, long hours, and poor operating conditions. The AFL paralyzed part of the metallurgical industry in the 35,000-year strike, not easy an eight-hour day, higher salary and union recognition. Steel corporations have retreated sharply, presenting metallurgists, a labor force made up largely of immigrants, as radical threats to American society. The strike failed and the metal industry saw virtually no industrial union organization for more than a decade.

Rail maintenance and repair staff called for a strike when the Rail Labor Commission cut their salaries by 7 cents an hour, an overall relief of 12%. Nearly 400,000 rail employees across the country have left their jobs. Strikebreakers were hired to update the original staff, and followed work-related violence and pickets. U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty nevertheless ended the strike by calling for a federal ruling to include an injunction opposed to the strike and the organization, which technically violates First Amendment rights. However, these occasions led to the Rail Labour Act 1926, which allowed railway staff to unionize.

During the 82-day strike, stevedores from all West Coast cities withdrew from their jobs and demanded an indefinite, much lighter union and more men in line with the ship cargo team. After violence erupted, divisions broke out between the docker and seafarers’ unions, and Roosevelt’s leadership has been concerned in an attempt to end the strike. The other people in the Stevedore were identified as a seaside-sized union, in line with wages and a union-controlled recruiting room.

The 113-day strike through United Auto Workers opposed the General Motors component of a series of primary strikes in the years after World War II. With the end of the war economy, which had kept wages low, the UAW, led through Walter Reuther, prevented production, was not easy a 30% pay increase and asked GM to avoid the artificial increase in car costs through the “planned sautomobilecity”, which led to lost jobs. In the end, the UAW and GM opted for a 17.5% pay increase, overtime and paid leave.

At the height of an eight-month national strike organized through the United Mine Workers of America to demand benefits and higher physical fitness wages, the U.S. government proposed an agreement with the union known as The Promise of 1946. The promise dictated that minors would get a pension and pension, as well as a separate fitness fund. It’s a pivotal moment in the history of miners’ labor rights.

When the school board on Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville network transferred more than a dozen white Jewish teachers and principals from its predominantly black and Hispanic schools, the United Federation of Teachers rejected the council’s action as anti-Semitic. Essentially, black parents and principals believe that black teachers deserve to teach their children. When white teachers tried to return to work, many network members and board-supporting teachers blocked their way, leading to a 36-day closure of local public schools. Eventually, the New York State Education Commissioner took the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district and rehired the transferred teachers.

Postal staff in New York and other cities in the country ceased to function for 8 days due to low wages and poor operating conditions. A meager salary of 5.4% accumulated out of 41% in Congressional salary provoked the anger of postal staff, whose paintings of another 200,000 people led to the advent of the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970. This law combined major trade unions in the ease of collective bargaining rights.

Phelps Dodge Corporation faced union leaders when copper costs fell in 1981 and the company fired thousands of employees. In the end, Phelps Dodge was able to stay afloat, reduced the cost-of-living adjustment of miners’ contracts, set physical care fees for staff, and reduced new employees’ salaries. As the strike progressed, the National Labor Relations Board gave its approval when staff voted to revoke thirteen Phelps Dodge-related unions, the largest decertification in the history of U.S. hard work.

Six unions and 2,500 others were in the midst of the long newspaper strike that lasted more than a year after the control of Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News to overwhelm unions by hiring independent contractors rather than publishers. Detroit newspapers continued to be published despite the strike and strikers began publishing their own newspapers. However, many strikers eventually repainted for Free Press and The News, and the unions ended the strike due to high costs.

After the merger of Bell Atlantic and GTE to shape Verizon, the new company will move outlets and offices to non-unionized locations, forcing many employees to move or lose their jobs. In the sensibleest of that, the staff had to work overtime. Nearly 85,000 members of the U.S. Communications Workers’ Unions and the International Brotherhood of Electricity Workers went on strike for 18 days. The strike ended when Verizon agreed to limit overtime to 10 hours according to the week and also granted a small payout to bilingual staff offering assistance to visitors in other languages.

Film and television writers from the Writers Guild of America went on strike to ask for a higher salary. The three-month strike resulted in the firing of many writers and production assistants, and the “Big Four” experienced a significant drop in prime-time ratings and had to struggle to locate content, which many say led to the rise of real television. . Training

In Chicago’s first teacher strike since the 1980s, the Chicago Teachers’ Union objected to the city of Chicago asking for salaries and higher plans, protections for teachers fired due to school closures, a program that included art, music and gymnasiums, fewer level tests for academics and smaller categories, among other things.

The very important strike concerned 20,000 teachers and staff in 55 state counties through the West Virginia branch of the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association. Teachers outdoors amassed the west virginia state capital in a fight for higher wages and lowered physical care costs. The strike ended when the West Virginia Senate approved a 5% pay increase; you may simply not be offering a solution to the rising costs of physical care. The action caused teachers in Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona and other states to strike for similar reasons in late 2018.

In 2018 and 2019, an average of 455,400 employees participated in primary paintpages, “the highest two-year average in 35 years,” according to the Institute of Economic Policy. Teachers continued their activities from 2018 to 2019, with educators from Los Angeles, Chicago, Denver, Oakland, Sacramento, Nashville, North Carolina, and South Carolina involved in changes in instructors’ salary and state cuts to school budgets. The year 2019 has noticed an increase in the number of instructor unions that their strength to fight for broader disorders affecting their students. The Chicago instructor strike included calls for affordable housing, immigrant protection, and more cash for the city’s poor and neglected neighborhoods. The strikes in Chicago and L.A. resulted in more nurses and librarians in schools. The other primary strike of the year was that of the automotive staff. General Motors staff went on strike for 29 days. With 46,000 employees without working days, GM’s strike was the largest in terms of days of lost paints.

The Milwaukee Bucks never left their locker room to play their opposite game to the Orlando Magic on August 26, and went on strike to protest the police shooting of black man Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. In a quick succession, the Milwaukee Brewers announced that they would not play their game that night; the rest of the NBA games of the night have been postponed; and professional football, tennis, women’s basketball and baseball games were canceled. This is an unprecedented wave of pro-athletic activism. The Bucks called on the Wisconsin legislature, which has been dormant for months, to call a consultation to discuss police reform.

The data on this page is provided through a separate external content provider. Frankly, and this makes no promises or representations about it. If you are affiliated with this page and want it to be deleted, tap [email protected]